The Entrepreneurial Transformation: Habits, Identity, and the Courage to Imagine Otherwise

A Critical Essay on Why Entrepreneurship Is a State of Mind, and Why Most People Never Achieve It

PART 1: THE JOURNEY: FROM ORDINARY AMBITION TO LIVED REALITY

The Obsession That Precedes Becoming

There exists a peculiar phenomenon in those drawn to entrepreneurship: a kind of relentless intellectual engagement with the question of possibility.

From my teenage years onwards, I was obsessed with it, not with specific business ideas, but with the principle itself. I consumed stories of founders, read about market dynamics, imagined solutions to problems I saw daily, and watched my dad in action. This obsession, I would later understand, was not entrepreneurship itself. It was the precursor, the vision without the muscle, the dream before the discipline.

That obsession, however, did not translate automatically into action or identity. For years, I remained an employee. A competent one, perhaps even ambitious by conventional metrics. I excelled at what was asked of me. I moved to cities, accumulated credentials, built professional networks. To external observers, this was success. But internally, there existed a profound misalignment, a cognitive dissonance between who I believed I could become and who I was being asked to be. None of it motivated me.

The Comfort Zone as a Psychological Trap

The employee years were characterized by what psychologists call status quo bias, a preference for maintaining the existing state even when alternatives offer greater benefits. This bias is not stupidity or laziness. It is a sophisticated cognitive defense mechanism rooted in loss aversion. The brain, when evaluating change, weighs potential losses far more heavily than potential gains. A 30% salary increase feels insignificant compared to the security of the known routine.

More insidiously, the comfort of employment depletes the cognitive resources necessary for imagining alternatives. Status quo bias persists partly because changing one’s mind about one’s career requires the expenditure of mental energy to analyze options, foresee consequences, and commit to uncertainty. When your current role satisfies basic needs, payment, status, structure, the brain economizes by simply choosing the default option: tomorrow will be like today.

There is a paradox that many people never recognize: remaining in a comfortable position is actually the riskier choice. Employment offers the illusion of safety while exposing you to forces entirely outside your control, organizational restructuring, technological disruption, economic recession, managerial capriciousness.

The 2008 financial crisis and subsequent pandemic demonstrated this brutally: millions discovered that their ‘safe’ jobs were not safe at all. The perceived security was, all along, an accident of circumstance.

Entrepreneurship, by contrast, places control into your own hands. The risk is real but managed by you, determined by your decisions, responsive to your effort. Yet it feels subjectively more dangerous because it is more visible, less insurable, less culturally normalized.

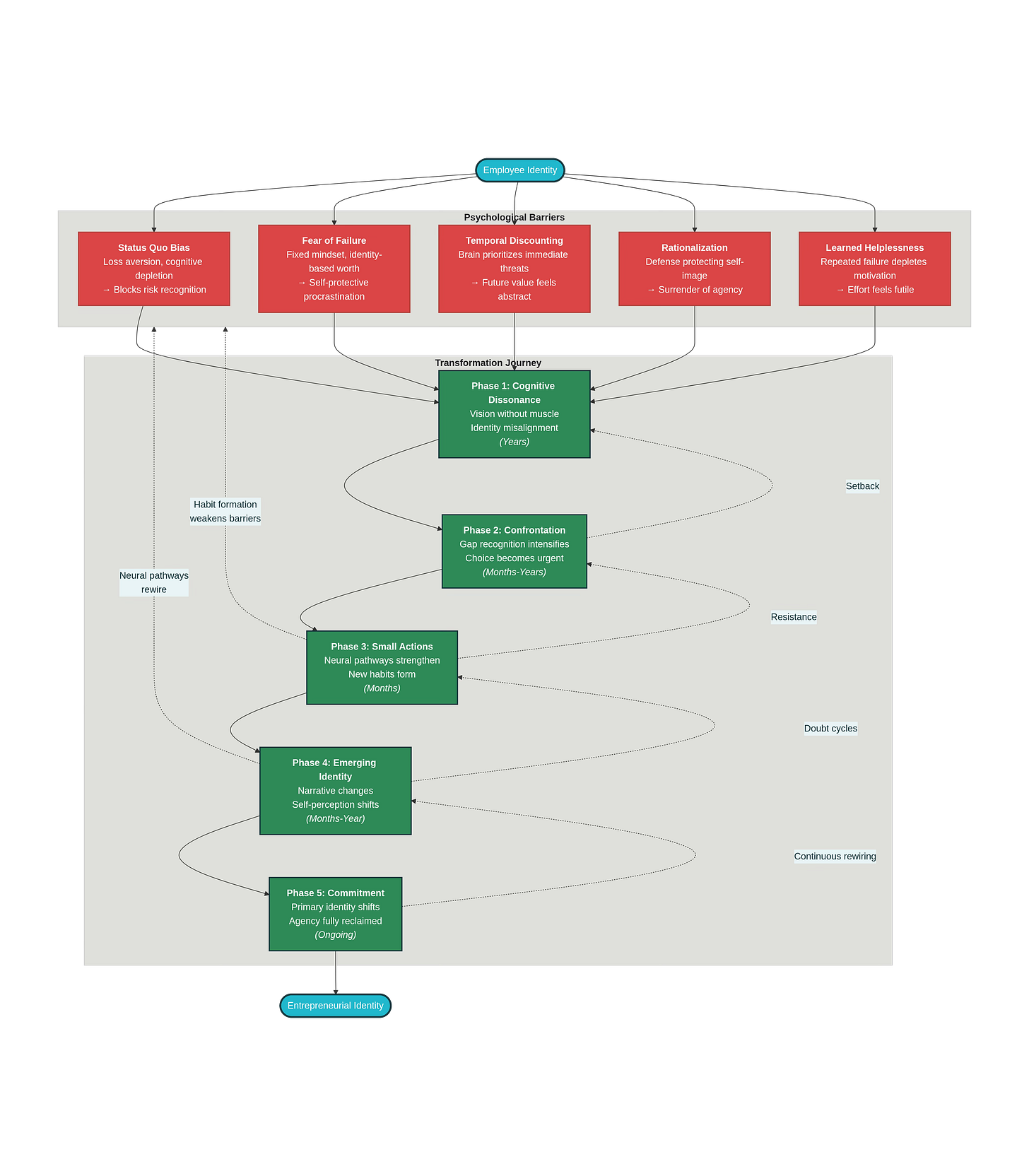

The Psychological Architecture of Transformation

The transition from employee to entrepreneur requires more than a decision. It requires an identity shift. Identity Theory, rooted in psychological research, reveals that our sense of self is constructed through the roles we occupy. When you occupy the role of ‘employee’, your daily rhythms, social interactions, mental frameworks, and even your neural pathways become organized around that identity. You internalize its expectations, adopt its values, and your brain literally rewires to make the associated behaviors automatic.

To become an entrepreneur is not merely to change your job title. It is to fundamentally reconstruct your sense of who you are and what you are capable of becoming. This reconstruction is neither quick nor costless.

In my own experience, this reconstruction occurred in distinct phases:

Phase One: Cognitive Dissonance and Discontent (Ages 18-28)

During this period, I was intellectually committed to entrepreneurship but behaviorally committed to employment. I read extensively, imagined scenarios, even sketched business models. Yet I took no action that genuinely risked my security. I had what I now recognize as a fixed mindset - I believed that successful entrepreneurs possessed some innate trait I might or might not have, and that attempting without certainty of success was foolish. This phase was characterized by what psychologists call self-protective procrastination. By not attempting, I protected myself from discovering that I might lack the necessary talent.

Phase Two: Confrontation with Reality (Ages 28-32)

At some point, and this point varies for different people, the gap between aspiration and reality becomes unbearable. For me, it was not a dramatic crisis but a slow-building recognition: if I did not act now, I would never act. My career trajectory was increasingly constrained. The compensation was rising but the freedom was declining. Organizational structures were calcifying around me. I was becoming more comfortable, which paradoxically made the idea of leaving more terrifying.

This phase involved facing down my own fear. Not the absence of fear, but the recognition that fear was not a valid reason for inaction. Fear, I learned, is not a signal of true danger. It is a signal of the unfamiliar. And entrepreneurship is, by definition, unfamiliar.

Phase Three: Small Actions and Emerging Identity (Ages 32-35)

I began to take small steps outside my primary employment. I built things for which nobody paid me. I gave away my knowledge through conversations. I formed partnerships with individuals who shared the obsession. These actions were modest, they did not consume my entire identity or income, but they were real.

What happened next is scientifically explicable through neuroscience. The brain’s basal ganglia, the region responsible for habit formation and motor control, begins to respond to repeated behavior by strengthening neural pathways. When you repeat an action, neurons form stronger connections. This process, called myelination, insulates neural pathways, making the behavior more efficient and automatic. With each small entrepreneurial action, each conversation, each experiment, each iteration, my brain was reorganizing itself. The psychological identity of “entrepreneur” was not being assumed. It was being built.

Simultaneously, a shift occurred in my narrative identity, the internalized story I told myself about who I am and what I am capable of. Instead of narrating myself as ‘someone interested in entrepreneurship’, I began to narrate myself as ‘someone who builds things’.

This shift from aspirational description to identity-based narration is far more powerful than it might initially appear. Research on narrative identity shows that the way we frame our life experiences', the emotional tone, the causality, the meaning we extract, shapes not only our psychological well-being but our future behavior.

Phase Four: Commitment and Reconstruction (Ages 35-Present)

Eventually, I crossed a threshold. The entrepreneurial identity became primary. Employment became secondary. At this point, the discomfort inverted: the thought of returning to traditional employment now felt like the greater risk, the greater loss.

I am not going to pretend this phase has been linear or unambiguously positive. Entrepreneurship carries real costs, financial unpredictability, constant problem-solving, the emotional weight of decisions that affect others’ livelihoods, the loneliness of making choices that no consensus validates. But these costs feel worth the price because they are the costs of agency. I am no longer a passenger in my own career. I am the pilot.

The Visible Emergence of Pattern

What I observe now, looking back across these phases, is not a man transformed overnight but a man in whom patterns have gradually assembled into a new configuration. The obsession that began in adolescence, the skills accumulated through employment, the networks developed through various roles, the failures I have experienced and learned from, all of these elements are now coherent. The picture is not yet complete. There will be more learning, more failure, more iteration. But for the first time, the outlines are visible.

This is what transformation looks like when it is genuine: not revelation but gradual reorganization. Not certainty but increasing confidence in one’s capacity to navigate uncertainty. Not the elimination of fear but the decision that fear is not the relevant metric.

PART 2: THE HIDDEN BARRIERS: WHY ENTREPRENEURSHIP REMAINS SO DIFFICULT

A Reframing of the Problem

The question most people ask is: ‘What does it take to become an entrepreneur?' But this is the wrong question. The correct question is: ‘What prevents the vast majority of talented, ambitious people from becoming entrepreneurs, when the barriers to entry are objectively lower than ever before?’

We live in an era of historically unprecedented opportunity. Digital tools cost nearly nothing. Capital can be accessed through multiple channels. Knowledge is freely available. And yet, the percentage of people who actually build something meaningful remains vanishingly small. The barrier is not external. It is internal.

The Architecture of Comfort

Psychologists have identified a phenomenon called the comfort zone, a psychological state in which anxiety is minimized and performance is stable. The comfort zone is not, as colloquial language suggests, a place of great comfort. Rather, it is a place of equilibrium. The brain prefers equilibrium because equilibrium is predictable, and predictability allows for efficient functioning without constant alertness.

When you step outside your comfort zone, several things happen simultaneously:

Cognitive Load Increases: Your brain must consciously attend to novel stimuli and choices. This requires metabolic energy. Unlike activities performed on automatic pilot (which consume minimal cognitive resources), novel activities demand constant conscious attention.

Anxiety Rises: Because outcomes are uncertain, your amygdala, the brain’s threat-detection system, activates. You experience physiological stress responses: elevated cortisol, increased heart rate, reduced parasympathetic activation.

Performance Initially Decreases: Because your cognitive resources are divided between task execution and threat monitoring, you perform worse in the short term than you would in familiar territory. Personally, I have a lot of stories to tell about this phase of mine!

Gratification is Delayed: The rewards of entrepreneurship are abstract and distant. You might spend months building something that no one buys. The comfort zone, by contrast, offers immediate, tangible rewards: a paycheck, recognition from your manager, the security of a known outcome.

This architecture explains why the comfort zone is so persistent. It is not simply inertia. It is a sophisticated equilibrium maintained by real neurological and psychological mechanisms.

Fear of Failure as Identity Protection

Beneath most resistance to entrepreneurship lies a fear that is rarely articulated in its true form. It is not primarily fear of financial loss (though that is real). It is fear of identity failure, the terror that if you try and fail, you have proven something undesirable about yourself.

Psychologists have documented this pattern extensively. People who fear failure tend to have what researcher Carol Dweck calls a fixed mindset, the belief that ability is a static trait determined at birth. In this worldview, success proves you are talented, and failure proves you are not. The stakes of attempting are thus existential. You are not merely testing a business hypothesis. You are submitting your fundamental worth to judgment.

This fear expresses itself through a process called self-handicapping. Unable to succeed, the person manufactures an excuse that protects their self-image. ‘I didn’t really try.’ ‘I was too busy.’ ‘I didn’t have enough capital.’ ‘The market wasn’t ready.' ‘I was too old/young.’ These are not lies exactly, but they are protective distortions. By attributing failure to external circumstances rather than internal capability, a person preserves their sense of self-worth.

I actually have very capable friends who have been talking of their brilliant ideas for more than a decade, and about their capability in executing them. They aren’t wrong, but I also know that they will never take action.

The tragic irony is that this self-protection strategy is self-defeating. By not fully committing, by maintaining an excuse-ready narrative, the person ensures that they will not learn the skills necessary for success. The excuse becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy.

The Temporal Problem: Discounting the Future

A new branch of psychology has illuminated a previously under-recognized problem: humans are neurologically wired to discount the value of future rewards relative to present rewards. This phenomenon, called temporal discounting, is not a character flaw. It evolved because it was once advantageous. In environments where the future was genuinely uncertain, prioritizing immediate rewards was rational. You took the food in your hand rather than gambling on what might appear tomorrow.

But in modern environments, this neurological inheritance becomes maladaptive. Entrepreneurship requires the opposite calculation: you sacrifice present comfort for future possibility. You forgo immediate income and security for the promise of future autonomy and impact.

The typical pattern is thus predictable:

A person identifies an opportunity. The initial enthusiasm is high. But as the opportunity requires sacrifice of present comfort, working evenings while maintaining employment, learning new skills that demand time, risking capital that could provide security, the discounted value of future reward fails to overcome the immediate cost. The amygdala’s threat-detection system, which is highly attuned to immediate threats, generates anxiety about present loss. The reward system, which is attuned to immediate gratification, finds the delayed reward underwhelming.

The person procrastinates. And as the deadline (or more accurately, the moment of irreversible opportunity cost) approaches, urgency might spike motivation briefly. But often, the window closes. The person returns to the comfort zone, now armed with a narrative: ‘I tried entrepreneurship and it wasn’t for me.’

Rationalization: The Intelligent Person’s Trap

Of all the mechanisms that keep people trapped in non-entrepreneurial lives, perhaps none is more insidious than rationalization. Rationalization is a psychological defense mechanism in which a person constructs a seemingly logical explanation for behavior that is actually driven by unconscious motives.

The mechanism operates like this: A person has a strong desire to pursue entrepreneurship, but also a strong fear of failure. These desires are in conflict, creating psychological discomfort (cognitive dissonance). To resolve this discomfort without facing the anxiety that entrepreneurship produces, the mind generates a plausible-sounding reason to abandon the entrepreneurial path.

And here is the crucial point: the rationalization often contains kernels of truth. ‘I don’t have enough capital.’ (True, capital is a constraint, though not necessarily an insurmountable one.) ‘I have family responsibilities.’ (True, though millions of entrepreneurs have navigated similar responsibilities.) ‘The market is saturated.’ (Partially true, and every mature market has multiple winners.) ‘I’m not smart enough.’ (Almost never true, but the person has constructed narratives of past failures that support this belief.)

Because the rationalization contains truth, the person can believe it. They are not consciously deceiving themselves. From their perspective, they have simply recognized an immutable reality. The rationalization protects them from the anxiety of attempting something difficult and uncertain.

The devastating irony is that this defense mechanism, by protecting short-term emotional comfort, ensures long-term psychological suffering. Research on narrative identity shows that the stories we tell ourselves about our lives predict our psychological well-being. People who view themselves as passive, constrained by circumstance, unable to influence outcomes, these people report lower life satisfaction, higher rates of depression, and less sense of meaning. They have traded short-term comfort for long-term despair.

The Social Dimension: When Context Constrains Agency

It would be incomplete to suggest that the barrier to entrepreneurship is purely individual psychology. Social structures and cultural expectations powerfully shape what feels possible.

A person’s immediate social context, their family’s attitudes toward risk, their friends’ career choices, their culture’s narratives about what constitutes a good life - creates what sociologists call social norms. These norms are internalized as expectations. If no one in your family has ever run a business, entrepreneurship may feel not merely risky but culturally alien.

Furthermore, institutional structures create genuine constraints. Access to capital, mentorship, and networks is highly unequal. Some people inherit social capital; others must build it from zero. A person raising children while working a full-time job has less discretionary time than a single twenty-five-year-old. These are not merely psychological obstacles. They are structural ones.

Yet even within these structural constraints, there is typically more agency than people recognize. The person who says ‘I can’t start a business because I have a family’ might more accurately say ‘Starting a business while supporting a family would be very difficult and would require trade-offs I’m not willing to make.’ The second statement is more honest and more actionable. It acknowledges constraint while preserving agency.

The Illusion of Knowledge as Barrier

Finally, a subtle barrier deserves mention: the belief that one needs vastly more knowledge before beginning. Successful entrepreneurs are often portrayed as visionaries with deep expertise. The aspiring entrepreneur compares their knowledge to this idealized image and concludes they are not ready.

But research on entrepreneurial cognition shows that successful entrepreneurs typically begin with far less knowledge than they think they need. They learn through iteration - building, testing, receiving feedback, adjusting, building again. The knowledge is constructed through action, not accumulated in advance.

This too is partly a rationalization. ‘I need to learn more’ is a socially acceptable reason to postpone action. And learning is genuinely valuable. But there is a threshold beyond which additional learning becomes procrastination. The person is studying the map when they should be walking the terrain.

PART 3: THE LAMENT: WHY I CANNOT SHAKE AWAKE THOSE CLOSEST TO ME

The Impossible Conversation

Over the past several years, I have watched people close to me, talented, intelligent, ambitious people, remain locked in professional situations that visibly constrain them. I have attempted, in various ways, to suggest alternatives. The conversation is invariably the same, and invariably leads nowhere.

They will see, they say. They will evaluate. They are planning to make a change... in two years, after they have paid off debt, after they get that promotion, after they buy a house, after their child finishes school. The future is always the appropriate time for action. The present is always constrained by obligations.

When I suggest that waiting for perfect conditions is itself a choice, a choice that compounds with every year, they respond with a litany of reasons why their situation is different. They have more responsibilities. They have more to lose. They are less skilled. They are too old. They are too young. They haven’t found the right idea yet.

The Architecture of Excuse

What I have come to understand is that these are not failures of intelligence or courage. They are failures of framing. The person has constructed a coherent, internally consistent narrative in which inaction is justified. And because the narrative is constructed by their own mind, because it explains many genuine constraints, it feels like truth.

But the narrative serves a psychological function beyond describing reality. It protects the person’s sense of self-worth. If the person could begin an entrepreneurial venture but chooses not to, they must confront the question: ‘What am I giving up by not trying? What am I choosing comfort over?’ This question generates anxiety.

It is far more comfortable to construct a narrative in which the choice is not one- in which action is simply not possible given current circumstances. The narrative of constraint is a defense mechanism.

I observe this mechanism with particular clarity in people who voice elaborate excuses:

‘I’m too busy.’ (Yet they spend hours on leisure activities. The issue is not time but priority and willingness to tolerate chaos.)

‘I don’t feel ready.’ (Readiness is largely a feeling, not a factual state. Entrepreneurship builds readiness through action, not through waiting for feelings to align.)

‘I need more money.’ (Many businesses start with minimal capital. The issue is not capital but willingness to experiment with constraint.)

‘I’m not good enough.’ (Compared to whom? The successful entrepreneurs they admire started exactly where they are now, or worse.)

‘I have too many responsibilities.’ (True, and they have chosen these responsibilities, continue choosing them daily, and use them as justification for not choosing differently.)

The tragedy is that each excuse contains a seed of truth. There are real constraints. Responsibility is real. But the person has mistaken constraint for impossibility. They have confused ‘this is difficult’ with ‘this cannot be done.’

The Identity Trap: Being vs. Becoming

What I have come to recognize is that the core issue is not the constraints themselves but the person’s identity. They have come to identify as ‘someone who is not an entrepreneur’. And this identity, while comforting, is also limiting.

Identity Theory suggests that we organize our behavior around the roles and identities we have adopted. When a person identifies primarily as an ‘employee’, they think, feel, and act in ways consistent with that identity. To become an entrepreneur requires not merely changing behavior but reconstructing identity, and identity reconstruction is psychologically costly.

Moreover, there is a self-fulfilling prophecy at work. The person who identifies as ‘someone who is not entrepreneurial’ makes choices consistent with that identity. They avoid risk. They do not initiate. They wait for instruction. And these choices produce evidence that confirms the identity: ‘See, I made the safe choice, which proves I am risk-averse.’

What they do not recognize is that the identity itself is constructed through these choices. The person is not risk-averse by nature. They have become risk-averse through years of choosing safety. And this construction, though it took years to develop, is not immutable. It can be reconstructed.

But reconstructing identity requires what psychologists call disconfirming evidence, experiences that contradict the existing identity narrative. The person must do something that contradicts their self-concept. This is uncomfortable. The brain prefers consistency. And so the person avoids disconfirming evidence. They do not attempt things that would prove them capable, because the attempt itself is identity-threatening.

The Learned Helplessness Problem

In some cases, the barrier is even deeper. Some people have developed what psychologists call learned helplessness, a learned belief that their actions do not produce outcomes. This belief, once established, becomes self-perpetuating.

Research shows that when people repeatedly experience situations in which their efforts do not produce desired results, they eventually stop trying. They do not consciously decide that trying is futile. Rather, their nervous system learns that effort is ineffective. The motivation system, deprived of evidence that action produces reward, shuts down.

For some of the people I know, this might be the operative mechanism. They have attempted change before and experienced failure. They may have lacked resources, poor timing, or simply poor execution. But the specific reasons fade. What remains is a generalized sense that ‘people like me’ do not become entrepreneurs. That this outcome is for others, not for them.

Breaking learned helplessness requires what coaches call ‘behavioral activation’ - taking action even when motivation is absent, even when the probability of success seems low. The person must generate small wins that provide evidence that effort produces outcomes. Only through repeated disconfirming experiences can the learned helplessness be unraveled.

Why This Matters (Beyond My Own Frustration)

My inability to ‘shake awake’ the people close to me was initially a source of frustration. I believed (with a certain arrogance) that if I could only articulate the right argument, they would see. They would recognize the trap they were in and escape it.

I have since recognized several things:

First, my role is not to convince them. People do not change through argument. They change through experience and through their own internal recognition of discrepancy between their values and their actions.

Second, the compassion lies in understanding rather than solving. The person who remains in a constrained career is not weak or stupid. They are navigating genuine constraints, financial, social, psychological, and structural. And they are doing so under the burden of the very psychological mechanisms I have described.

Third, there is a universal dimension to this struggle. If I have been ‘obsessed with entrepreneurship’, it is because I have been willing to tolerate the anxiety of not knowing, the uncertainty of outcomes, and the repeated experience of failure and iteration. Many intelligent people are not willing to tolerate these things. That is not a moral failing. It is simply the trade-off they have chosen.

But here is what troubles me: many of these people do not recognize that it is a choice. They experience their constraint as imposed rather than chosen. And this misframing, this attribution of agency to external circumstances rather than to themselves, is the source of long-term dissatisfaction. Research on narrative identity and locus of control shows that people who attribute outcomes to internal causes (their own choices and effort) report higher life satisfaction, even when circumstances are objectively difficult. People who attribute outcomes to external causes (luck, circumstances, others’ decisions) report lower satisfaction and higher rates of depression.

The tragedy is not that they remain in non-entrepreneurial careers. The tragedy is that they have surrendered their sense of agency in the process.

PART 4: THE FUTURE: WHERE THIS IS HEADING

The Acceleration of Choice

We are entering an era in which the ability to create and distribute value is becoming radically democratized. This is not new to observe - commentators have noted this for years. But the implications are only now becoming clear.

The traditional career ladder, which could absorb a person’s talents and provide security in exchange for loyalty, is dissolving. Organizational structures that once provided stability are now fragile. Industries are being disrupted every five to ten years. The average job tenure continues to decline.

Simultaneously, the tools and infrastructure for creating value independently are improving exponentially. What required tens of thousands of dollars and years of learning fifteen years ago now requires hundreds of dollars and weeks of learning. The barrier to entry has been systematically lowered.

These twin trends - declining security in traditional employment and declining barriers to independent value creation, suggest that the future will be characterized not by more security but by more choice. People will not be able to opt into stability. They will have to construct their own.

This shift, while terrifying to many, creates an enormous opportunity. For those who develop the habits, mindsets, and skills of entrepreneurship, the future is abundant. For those who continue to expect security and stability from organizations, the future will be characterized by increasing anxiety.

The Mindset Imperative

What will distinguish those who thrive from those who merely survive in this future is not technical skill or business acumen alone. It is mindset - specifically, a growth mindset.

Psychologist Carol Dweck’s research shows that people with a growth mindset, who believe that abilities are developed through effort, are far more likely to persist in the face of difficulty, to learn from failure, and to achieve long-term success. People with a fixed mindset, who believe that abilities are innate, tend to give up when challenged and to avoid situations that might reveal limitation.

In a world of increasing uncertainty and constant disruption, the growth mindset is not a luxury. It is a prerequisite for psychological survival. The person who believes that their skills are fixed and their trajectory is determined will experience the future as a series of threats. The person who believes that their capabilities can be developed will experience the future as a series of opportunities.

The good news is that mindset is not fixed. Research shows that exposure to evidence of neuroplasticity, combined with deliberate practice and reflection, can shift people from a fixed to a growth mindset. But this shift requires intentional effort. The default is to slide toward fixed thinking.

The Emergence of Purpose-Driven Work

There is another trend operating simultaneously, one that offers hope. Particularly among younger generations, there is a growing recognition that work is not merely instrumental (a means to earn income) but existential (a means to express identity and contribute meaning). This shift is creating a crisis for traditional employment - people are abandoning lucrative careers because the work lacks meaning.

Entrepreneurship, by contrast, offers something employment rarely provides: the ability to construct work that is aligned with your values and vision. You are not executing someone else’s strategy. You are exploring your own questions.

This is not sentimental. It is psychological necessity. Research on meaning in life shows that people who experience their work as meaningful report higher well-being, greater resilience in the face of adversity, and stronger sense of purpose. Meaning in life, in turn, is one of the strongest predictors of hope - the psychological state of agency and pathway toward valued goals.

The future will belong to those who can construct meaningful work, not merely consume meaningful work designed by others.

The Dual Challenge: Psychological and Structural

None of this means the future will be easy or that entrepreneurship will be accessible to all. There will continue to be genuine structural barriers - access to capital, education, networks, that are unequally distributed. The democratization of opportunity is real but incomplete.

But for most people reading this, particularly those with education and basic security, the barrier is primarily psychological. And psychological barriers, unlike structural ones, are within your control.

This is where hope resides. You cannot change whether you were born into wealth or poverty, into a culture that values entrepreneurship or discourages it, into a family that provided mentorship or none. But you can change your mindset. You can change your habits. You can change the story you tell yourself about what is possible for you.

The neuroscience is clear: the brain rewires through repeated action. Small habits compound. Small wins build momentum. The entrepreneur you could become is not distant or impossible. It is an iteration away.

The Realistic Optimism Required

It would be false to suggest that the future is without risk. Entrepreneurship is difficult. Most new ventures fail. Income is uncertain. Work is constant. And yet these difficulties are not arguments against entrepreneurship. They are arguments for choosing it consciously.

The most successful entrepreneurs, research shows, are neither purely optimistic nor purely realistic. They are what might be called realistically optimistic. They see obstacles clearly. They do not overestimate their abilities. They plan for contingencies. But they maintain a baseline confidence that they can navigate difficulty if it emerges.

This balanced perspective is available to anyone willing to develop it. It requires seeing failure not as evidence of limitation but as data for improvement. It requires viewing obstacles not as signs to turn back but as information to incorporate.

The Call and the Possibility

If this whitepaper has one function, it is to articulate a possibility that most people never seriously consider: Your life could be fundamentally different. Not in a year, but in six months of intentional effort. Not through luck, but through the deliberate reconstruction of your habits, your identity, and your narrative.

The person you are today is not fixed. You are not locked in your career, your skills, your circumstances. You are the product of the choices you have made, and you can make different choices.

This is not false hope. This is neurological fact. The brain is plastic. Identity is constructed. Habits are learned. All can be reconstructed.

What is required is:

The willingness to tolerate discomfort. Growth exists outside the comfort zone. You will need to do things that feel uncertain, risky, and unfamiliar.

The shift from fixed to growth mindset. You must come to believe, not sentimentally but practically, that your abilities are developed through effort. This shift alone changes how you respond to failure.

The initiation of small, consistent action. You do not need a perfect plan or complete knowledge. You need to do something real, something that produces feedback, something that contradicts your current limiting narrative about yourself.

The reconstruction of your identity narrative. Stop narrating yourself as ‘someone who is interested in entrepreneurship but hasn’t started.’ Begin narrating yourself as ‘someone who builds things.’ This shift is not just semantic. It changes how you allocate attention, how you make decisions, and what you notice in your environment.

The courage to imagine a future that is not predetermined. Most people inherit their futures rather than construct them. They follow the path laid by education, family expectation, and career trajectory. Entrepreneurship requires imagining a future that is genuinely yours - not a fantasy, but a direction you are willing to move toward.

SUMMARY: A CALL TO ACTION AND AN OFFERING OF HOPE

The Inversion of Risk

We have been taught to view entrepreneurship as the risky choice and employment as the safe choice. This inversion has become so embedded in cultural narrative that it feels like truth.

But the evidence now clearly suggests the opposite. In a world of accelerating technological change and disruption, the safe choice is entrepreneurship, because it places you in control of your adaptation. The risky choice is employment, because it places you dependent on an organization’s ability to navigate change.

This is not an argument to quit your job tomorrow. It is an argument to recognize that your default narrative about risk is backwards. Once you see this inversion, you cannot unsee it.

The Democratization of Possibility

For the first time in human history, the means of value creation are not concentrated in institutions. They are distributed. A person with internet access and a laptop can reach global markets. They can learn any skill. They can test ideas with minimal capital.

The gatekeepers have been displaced. There is no longer a committee that must approve your right to attempt. You simply... attempt.

This is simultaneously terrifying and liberating. Terrifying because you cannot blame gatekeepers for your lack of success. Liberating because you can construct the future you genuinely want.

The Reconstruction of Meaning

Ultimately, the shift from employee to entrepreneur is not about money or status or power (though these may follow). It is about meaning.

Meaning, research shows, comes not from what you consume but from what you create. Not from what you are given but from what you choose. Not from the roles assigned to you but from the roles you construct for yourself.

People who describe their lives as meaningful, who report high life satisfaction, who persist through difficulty - these people tend to share one characteristic: they believe their choices matter, and they take responsibility for constructing their lives accordingly.

This is available to you. Not someday, when conditions improve. Not after you accumulate more resources or credentials or confidence. But now.

The obsession with entrepreneurship that I carried into adulthood was not a delusion or a character flaw. It was a recognition, however inchoate, that I did not want to inherit my future. I wanted to construct it.

That obsession, combined with small actions, with the willingness to fail repeatedly, with the patience to iterate, with the humility to learn, has led to a life that is genuinely mine.

This is what is possible for you. Not certainty. Not safety. But agency. Meaning. The deep satisfaction of having attempted something difficult and, through failure and iteration, having built something real.

The Final Lament and Hope

I lament that I cannot convey to those close to me the possibility that awaits them. I cannot make them feel the freedom that comes from agency, the meaning that comes from creating something, the hope that comes from believing your efforts matter.

But perhaps that is not my function. Perhaps my function is only to articulate the possibility, to model it through my own stumbling attempts, and to invite them to imagine differently.

For those who are willing to engage this imagination, to shift from ‘What if I fail?’ to ‘What am I giving up by not trying?’ - the future is abundant. It is not guaranteed. But it is genuinely possible.

The obstacles are real. But they are not insurmountable. And they are not external. They are internal—= - habits of thinking, stories we tell ourselves, identities we have inherited rather than constructed.

These can be changed. You can be the architect of your own becoming.

The question is not whether it is possible. It is whether you are willing to begin.

This whitepaper is an invitation to recognize that entrepreneurship is not a distant possibility for the exceptional. It is a mindset, a set of habits, and a narrative - all of which are within your capacity to develop. The future will be shaped by those who are willing to construct their own paths rather than inherit predetermined trajectories. That future can include you.