The Unquiet Engine: An Exhaustive History of Entrepreneurial Theory, Practice, and Ecosystem Evolution

Learning about the history of entrepreneurship in order to get better at living an entrepreneurial life as a non-negotiable.

Introduction

The history of economic progress is frequently recounted as a history of nations, technologies, or grand macroeconomic forces. Yet, beneath the aggregate statistics of GDP and the geopolitical maneuverings of empires lies the distinct, often chaotic, agency of the individual actor: the entrepreneur. This white paper provides a comprehensive, deep-dive analysis of the detailed history of entrepreneurship, tracing its lineage from the mercantilist adventurers of pre-industrial Europe to the algorithmic gig workers of the 21st-century digital ecosystem.

The scope of this inquiry is not merely chronological but theoretical and structural. To understand the modern entrepreneur, whether a Silicon Valley founder or a freelance creative, one must understand the intellectual heritage that defined their function.

We must traverse the definitions of Richard Cantillon, who first isolated the “uncertainty-bearing” function of the entrepreneur from the capital-holding function of the landlord.1 We must grapple with the Schumpeterian vision of the entrepreneur as a destructive force, one who shatters the status quo to forge new economic realities.3 And we must examine the sociopolitical oscillations that saw the entrepreneur celebrated as a “Captain of Industry” in the Gilded Age, vilified as a “Robber Baron,” marginalized by the “Organization Man” of the mid-20th century, and finally resurrected as the central hero of the Information Age.5

This analysis posits that while the forms of entrepreneurship have mutated in response to technological and institutional shifts, from the trade caravans of the 17th century to the venture-backed software startups of today, the core function remains immutable. That function is the exercise of judgment in the face of non-insurable uncertainty.

Whether arbitrating the price of wool in 1730 or validating a SaaS business model in 2024, the entrepreneur remains the sole economic agent willing to bridge the gap between the known present and the unknowable future.8

Part I: The Genesis of the Concept (Pre-Industrial to Early 19th Century)

The theoretical framework of entrepreneurship did not emerge in a vacuum; it was forged in the transition from feudalism to early capitalism. In the static world of the Middle Ages, economic roles were largely hereditary and fixed. It was only with the rise of mercantilism and the expansion of global trade routes that a new class of economic actor was required, one who could navigate the inherent risks of distance and time.

1.1 Etymological Roots and Early Usage

The word “entrepreneur” itself is a loanword from the French, derived from the thirteenth-century verb entreprendre, meaning “to do something” or “to undertake”.10 Its earliest connotations were not strictly commercial but kinetic and often martial. In the 16th and 17th centuries, the term was frequently applied to military commanders who “undertook” the risk of leading expeditions, or to engineers who contracted to build fortifications or cathedrals.12

This etymological lineage is significant. It imbues the concept with an inherent sense of activity and risk-taking. Unlike the static “owner” of land or the passive “holder” of capital, the entrepreneur is an active agent, a doer.

By the early 18th century, as the focus of European powers shifted from conquest to commerce, the term began to migrate into the economic lexicon, signifying an individual who undertook a business venture with no guarantee of profit.10

1.2 Richard Cantillon: The Discovery of Uncertainty

The intellectual “Big Bang” for entrepreneurship theory occurred with Richard Cantillon (1680–1734), an Irish-French banker and economist whose life was as adventurous as his theory. His seminal work, Essai sur la Nature du Commerce en Général (published posthumously in 1755), is widely considered the cradle of political economy.2

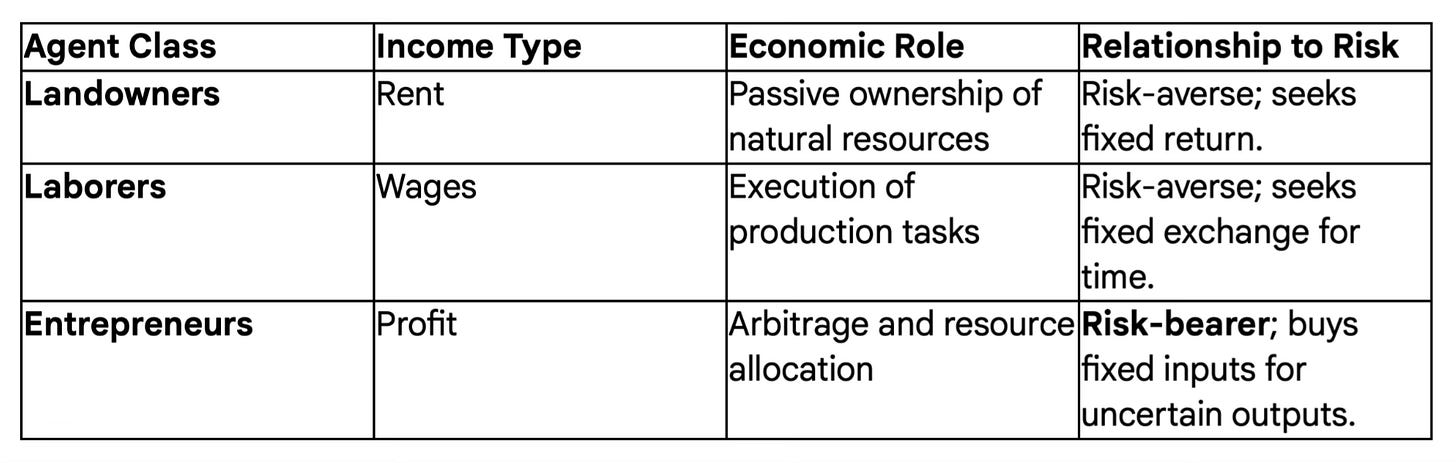

Cantillon was the first to rigorously distinguish the entrepreneur from other economic agents. In the physiocratic and mercantilist systems of his time, wealth was often equated with land or gold. Cantillon, however, looked at the mechanism of the market. He divided the economy into two principal classes:

The Hired: Those who receive fixed wages or annuities. Their income is contractually guaranteed (barring total systemic collapse).

The Entrepreneurs: Those who operate without fixed, secure earnings. Their income is residual and contingent on the success of their judgment.2

The Farmer-Entrepreneur Model:

Cantillon illustrated this with the example of the farmer. The farmer commits to paying the landlord a fixed rent (a known cost) at the beginning of the season. He then plants his crops, incurring further fixed costs for labor and materials. However, the price at which he will sell his harvest is unknown: it depends on the weather, the harvest of competitors, and the shifting tastes of consumers.

The farmer, therefore, buys at a certain price and sells at an uncertain price.1 This discrepancy is the domain of the entrepreneur.

Cantillon described this not merely as “risk” (which implies a calculable probability, like a dice roll) but as a fundamental uncertainty about the future state of the market. In doing so, the entrepreneur performs a vital social function: they absorb the uncertainty of the market, shielding the landlord and the laborer from the volatility of prices.2

Table 1: Cantillon’s Classification of Economic Agents

1

Cantillon’s theory was revolutionary because it decoupled the function of “entrepreneurship” from the social status of the actor. A beggar, a farmer, a merchant, and a manufacturer were all entrepreneurs if they lived by speculative income. This egalitarian economic view predated the formalization of capitalism, identifying the universal mechanism of uncertainty-bearing.2

1.3 Jean-Baptiste Say: The Entrepreneur as Optimizer

If Cantillon provided the risk component of entrepreneurship, the French classical economist Jean-Baptiste Say (1767–1832) provided the managerial component. Writing in the early 19th century, as the Industrial Revolution began to accelerate in France, Say witnessed the emergence of complex manufacturing systems that required more than just arbitrage; they required organization.13

Say coined the term’s modern economic usage in his Treatise on Political Economy (1803). He defined the entrepreneur as the agent who “unites all means of production - the labor of the one, the capital of the other, and the land of the third, and finds in the value of the products... the reestablishment of the entire capital he employs, and the value of the wages, the interest, and the rent which he pays, as well as the profits belonging to himself”.12

Say’s critical contribution was the distinction between the capitalist (who creates profit by lending money) and the entrepreneur (who creates profit by managing resources). He noted that the entrepreneur shifts economic resources “out of an area of lower and into an area of higher productivity and greater yield”.12

This definition frames entrepreneurship as an efficiency-seeking behavior. The entrepreneur is the super-intendent of the production process, the “master agent” who combines the passive factors of production into a living, value-creating organism.15

1.4 The British Omission: Smith, Ricardo, and Mill

Interestingly, the British classical tradition, dominated by Adam Smith and David Ricardo, largely neglected the entrepreneur. Smith’s Wealth of Nations (1776) focused heavily on the “capitalist” and the “undertaker” but rarely distinguished the two. In Smith’s model of the “invisible hand,” the market mechanism itself coordinated supply and demand, leaving little theoretical room for the creative agency of a specific entrepreneurial class.13

It was John Stuart Mill (1806–1873) who eventually bridged this gap in British thought. In his Principles of Political Economy (1848), Mill lamented that English usage had no specific word for the “undertaker” of industry, often conflating them with the capitalist. Mill adopted the French term entrepreneur to describe the person who assumes the risk and management of the business. He argued that profit was composed of three parts:

Interest (payment for abstinence/capital).

Insurance (payment for risk).

Wages of Superintendence (payment for the labor of management).15

Mill’s nuanced breakdown recognized that the entrepreneur was not merely a passive financier but an active worker, a manager whose skill and oversight were distinct factors in the success of the enterprise. This laid the groundwork for the modern understanding of the CEO-founder role.

Part II: The Age of Titans: Industrialization and the “Robber Baron” Paradox (1870–1920)

As the 19th century progressed, the scale of entrepreneurial activity underwent a phase shift. The Second Industrial Revolution, fueled by steel, oil, electricity, and railroads, created economies of scale previously unimaginable. The local merchant-entrepreneur of Cantillon’s day was replaced by the industrial titan, capable of mobilizing vast armies of labor and capital.

2.1 The Rise of the Industrial Entrepreneur

This era was defined by figures such as Cornelius Vanderbilt, John D. Rockefeller, Andrew Carnegie, and J.P. Morgan. These individuals did not just “shift resources” as Say had described; they built entirely new infrastructures that altered the geography and metabolism of the global economy.

Cornelius Vanderbilt (The Commodore):

Vanderbilt’s career epitomizes the transition from mercantilist trading to industrial infrastructure. Originally a steamship captain, he perceived the shift to railroads earlier than his peers. Vanderbilt is often cited by historians like Burton Folsom as a quintessential Market Entrepreneur. In the mid-19th century, the steamship industry was heavily subsidized by governments attempting to guarantee mail service and transport. Vanderbilt famously competed against these government-backed monopolies (political entrepreneurs) by ruthlessly cutting costs, improving efficiency, and lowering ticket prices, often to zero, to drive competitors out of the market before restoring them to profitable but reasonable levels. His success demonstrated that entrepreneurial efficiency could defeat state-sponsored privilege.

John D. Rockefeller (Standard Oil):

Rockefeller applied the concept of scale to the chaotic oil industry. Before Standard Oil, the kerosene market was volatile, dangerous (due to poor refining standards), and inefficient. Rockefeller utilized horizontal integration (buying competitors) and vertical integration (buying railroads, barrel factories, and pipelines) to squeeze inefficiency out of the supply chain. He reduced the price of kerosene by over 80%, illuminating working-class homes that previously relied on expensive whale oil.17

2.2 The “Robber Baron” Historiography

Despite their economic contributions, these figures were branded “Robber Barons,” a pejorative term coined by muckrakers and solidified by Matthew Josephson’s 1934 book The Robber Barons.5 The critique was that these entrepreneurs accumulated wealth not solely through innovation, but through:

Predatory Pricing: Undercutting competitors to drive them bankrupt.

Corruption: Bribing legislators for favorable tariffs and land grants (exemplified by the “Political Entrepreneurs” of the Union Pacific Railroad).

Labor Exploitation: Suppressing wages and unionization efforts.19

This dichotomy, ”Captain of Industry” vs. “Robber Baron”, reflects a fundamental tension in the history of entrepreneurship: the line between aggressive competition (which benefits the consumer through lower prices) and anti-competitive behavior (which harms the consumer through monopoly).

The Gilded Age forced society to confront the power of the entrepreneur, leading to the Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890, the first major legislative attempt to curb entrepreneurial excess.5

2.3 The Managerial Revolution and the Separation of Ownership

The sheer size of the industrial combines created a new problem: they were too large for any single individual or family to manage. This necessitated the “Managerial Revolution,” chronicled by historian Alfred Chandler. The “Visible Hand” of management, a hierarchy of salaried professionals, began to replace the direct oversight of the entrepreneur.19

By the early 20th century, the founder-entrepreneur (like Carnegie) was increasingly being replaced by the professional manager (like Alfred Sloan of GM). The entrepreneur became a figurehead or a financier, while the actual “superintendence” described by Mill was delegated to a bureaucracy. This structural shift set the stage for the theoretical debates of the 20th century regarding the “death” of the entrepreneur.

Part III: The Golden Age of Theory (1910–1960)

While the industrial world was bureaucratizing, economic theorists were finally giving the entrepreneur their due. The early 20th century produced the three pillars of modern entrepreneurial theory: Schumpeter, Knight, and Kirzner.

3.1 Joseph Schumpeter and Creative Destruction

Joseph Schumpeter (1883 - 1950) stands as the giant of entrepreneurial theory. In The Theory of Economic Development (1911) and Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy (1942), Schumpeter shattered the neoclassical assumption of “equilibrium.” For Schumpeter, the economy is a dynamic, evolutionary system driven by the “perennial gale of Creative Destruction”.3

Schumpeter argued that the function of the entrepreneur is innovation. This is distinct from “invention” (the creation of a new idea); innovation is the commercial application of that idea. The entrepreneur introduces “new combinations” into the market, which render existing technologies, products, and companies obsolete.

Schumpeter’s Five Forms of Innovation:

New Goods: Introducing a product with which consumers are not yet familiar.

New Methods of Production: Innovation in the process (e.g., the assembly line).

New Markets: Opening a market that had not previously been entered.

New Sources of Supply: Conquering a new source of raw materials.

New Organization: Creating a monopoly or breaking up an existing one.4

In Schumpeter’s view, the entrepreneur is a heroic, almost Nietzschean figure who fights against the social resistance to change. However, Schumpeter was pessimistic about the future. He predicted that the very success of the capitalist enterprise would lead to its stagnation. He believed that innovation would eventually be routinized within the R&D departments of large corporations, making the individual entrepreneur obsolete, a prediction that seemed all too real in the 1950s.4

3.2 Frank Knight: The Philosophy of Uncertainty

In 1921, American economist Frank Knight published Risk, Uncertainty, and Profit, providing the definitive distinction between “risk” and “uncertainty,” a concept that remains the bedrock of entrepreneurial finance.8

Risk: Relates to situations where the distribution of outcomes is known (e.g., actuarial risk in insurance). Risk can be hedged, insured, or calculated as a cost of doing business. It does not generate profit; it generates interest.

Uncertainty: Relates to unique situations where the probability of outcomes is unknowable (e.g., the success of a new fashion line or a revolutionary technology).

Knight argued that profit is exclusively the reward for bearing uncertainty. Since uncertainty cannot be contracted away or insured against, the entrepreneur acts as the residual claimant. They pay fixed wages to labor and fixed interest to capital, and in return, they claim the difference, if any exists. The entrepreneur’s social function is to exercise judgment in the absence of data.8

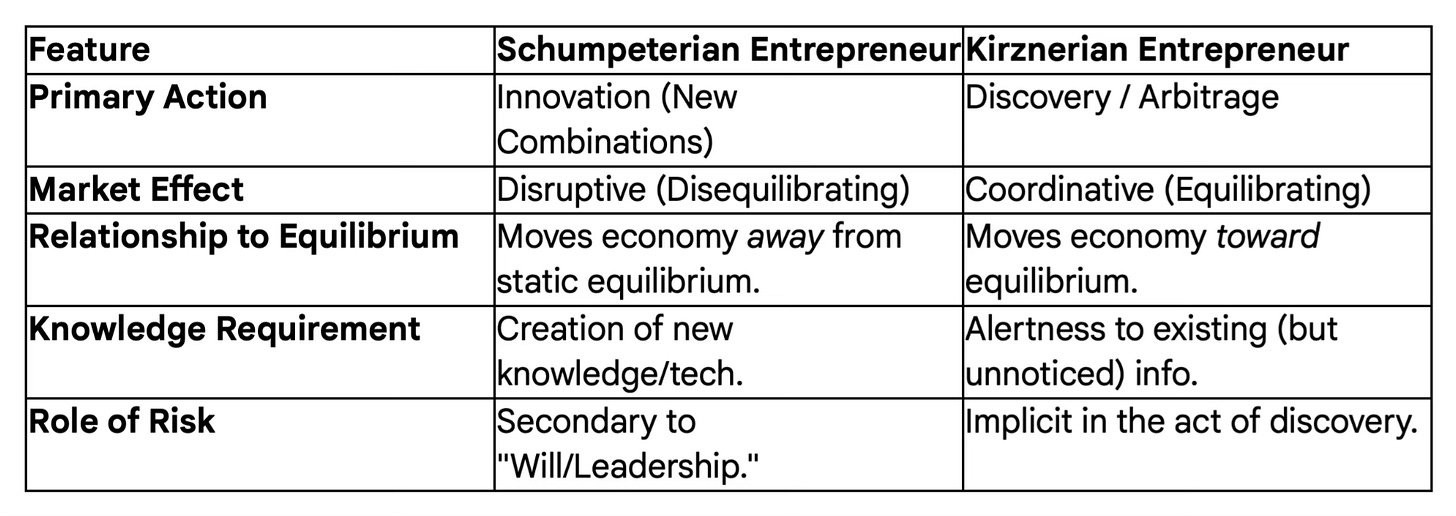

3.3 Israel Kirzner: The Alertness of the Arbitrageur

Countering the Schumpeterian view of the “disruptor,” Austrian economist Israel Kirzner (b. 1930) focused on the entrepreneur as an equilibrating force. In Competition and Entrepreneurship (1973), Kirzner introduced the concept of Entrepreneurial Alertness.21

Kirzner argued that markets are never in equilibrium due to ignorance. Information is widely dispersed and imperfect. The entrepreneur is the person who is “alert” to these imperfections, noticing, for example, that consumers are willing to pay more for a good than the cost of its resources. By acting on this opportunity (arbitrage), the entrepreneur corrects the error in the market and brings prices closer to their true value.

Table 2: Theoretical Divergence – Schumpeter vs. Kirzner

3

3.4 The Psychological Turn: McClelland’s “n-Ach”

In the 1960s, the inquiry shifted from what entrepreneurs do to who they are.

Harvard psychologist David McClelland, in The Achieving Society (1961), proposed that economic development is driven by a specific psychological trait: the Need for Achievement (n-Ach).25

Through experiments like the “Ring Toss,” McClelland found that high n-Ach individuals (entrepreneurs) differ from gamblers. Gamblers choose impossible odds (high risk), while conservative individuals choose guaranteed success (low risk).

Entrepreneurs, however, choose moderate risk where the outcome depends on their skill and effort. They desire personal responsibility and immediate feedback on their performance.27 McClelland argued that societies that cultivate this trait, through literature, child-rearing, and culture, experience faster economic growth, linking the macro-economy to the micro-psychology of the individual.28

Part IV: The “Organization Man” and the Bureaucratic Winter (1950–1970)

Despite the theoretical advancements, the mid-20th century reality was one of corporate hegemony. The Great Depression and World War II had consolidated economic power into massive conglomerates. The “American Dream” transformed from founding a business to climbing the corporate ladder at General Motors, IBM, or AT&T.

4.1 The Iron Cage of Bureaucracy

Sociologist Max Weber had earlier warned of the “Iron Cage” of rationality, where bureaucratic efficiency crushes the charismatic spirit of the entrepreneur.29 By the 1950s, this was the dominant social reality. William H. Whyte’s seminal book The Organization Man (1956) critiqued the new “Social Ethic” which valued conformity, belonging, and teamwork over the rugged individualism of the past.6

Whyte observed that the educational system and corporate culture were designed to produce “well-rounded” administrators who could maintain the system, not “wild spirits” who would disrupt it. The entrepreneur was often viewed with suspicion, as a relic of a chaotic, less civilized age. Stability, pension plans, and lifetime employment were the societal ideals.31

4.2 The Hidden Seeds of Disruption

However, even as the “Organization Man” dominated the cultural landscape, the seeds of his destruction were being sown. The corporate conglomerates were becoming bloated and risk-averse. They were structurally incapable of pursuing the radical innovations emerging in electronics and computing. This efficiency gap created the “Kirznerian opportunity” that would give birth to the Venture Capital industry.

Part V: The Renaissance – Venture Capital and the Silicon Valley Model (1970–2000)

The modern entrepreneurial ecosystem, characterized by high-growth startups, equity compensation, and venture financing, was invented in the post-war era. It was a deliberate restructuring of how risk capital met innovation.

5.1 Georges Doriot and the Invention of VC

The birth of modern Venture Capital (VC) is traced to 1946 with the founding of the American Research and Development Corporation (ARDC). The key figure was Georges Doriot, a French-born Harvard professor and former US Army Brigadier General. Doriot believed that the “G.I.” generation and university researchers held untapped potential that banks (who required collateral) would not fund.32

ARDC was the first publicly traded investment firm dedicated to funding private companies. Its validation came with its 1957 investment of $70,000 in Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC). By 1968, that stake was worth over $355 million, a return of over 500x.7 This “home run” proved that a portfolio of high-risk, high-tech investments could outperform the broader market, establishing the economic viability of the VC model.

5.2 The Traitorous Eight and Arthur Rock

While Boston (ARDC) provided the structure, California provided the culture. In 1957, eight scientists working for Nobel laureate William Shockley resigned due to his erratic management. This group, known as the “Traitorous Eight,” wanted to start their own semiconductor company but had no capital.

Investment banker Arthur Rock helped them secure funding from Sherman Fairchild, launching Fairchild Semiconductor.32 This deal is widely considered the first VC-backed startup in Silicon Valley. It established two critical precedents:

Equity for Founders: The scientists were not just employees; they were owners.

The Spin-off Culture: The “Fairchildren”, employees who left Fairchild to start their own companies (including Intel, AMD, and Kleiner Perkins), created the dense network of startups that defines the region today.7

Arthur Rock later founded Davis & Rock in 1961, pioneering the limited partnership model that dominates VC today. He funded Intel and Apple, cementing the role of the VC not just as a financier, but as a strategic partner and board member.32

5.3 The Bayh-Dole Act: Unleashing University Innovation

A critical legislative catalyst arrived in 1980 with the passage of the Bayh-Dole Act. Previously, the US government retained ownership of any invention created with federal funding. As a result, nearly 28,000 patents sat dormant in government archives because companies refused to license them without exclusive rights.34

The Act allowed universities and non-profits to retain title to these inventions and license them to the private sector. The impact was seismic:

Startup Creation: Since 1980, over 19,000 startups have been formed based on university research.

Economic Value: These innovations contributed an estimated $1.9 trillion to US industrial output.34

Sector Impact: The biotech industry, in particular, owes its existence to this transfer of basic science from university labs to venture-backed startups.

5.4 The Dot-Com Boom and Cultural Mainstreaming

By the late 1990s, the internet fueled a mania of entrepreneurial activity known as the Dot-Com Bubble. The NASDAQ index rose from under 1,000 in 1995 to over 5,000 in 2000.37 This era popularized the “Get Big Fast” strategy, prioritizing market share (”eyeballs”) over profitability.

Culturally, the Dot-Com boom replaced the “Organization Man” with the “Hoodie-Wearing Dropout” as the new American hero. It normalized the idea of quitting a stable job to pursue a high-risk venture. While the bubble burst in 2000, wiping out trillions in wealth, it left behind the broadband infrastructure and the social acceptance of risk that powered the next wave of Web 2.0 giants (Google, Facebook, Amazon).38

Part VI: Modern Methodologies and Fragmented Ecosystems (2000–Present)

In the wake of the Dot-Com crash, the practice of entrepreneurship underwent a rigorous professionalization. It moved from an art based on “gut feeling” to a science based on data.

6.1 The Lean Startup Revolution

The high failure rate of Dot-Com companies led serial entrepreneur Steve Blank to rethink the startup process. He realized that startups failed not because they couldn’t build technology, but because they built products nobody wanted. In The Four Steps to the Epiphany (2005), Blank introduced Customer Development, arguing that “startups are not smaller versions of large companies”.40 Large companies execute known business models; startups must search for them.

Blank’s student, Eric Ries, combined this with Agile software development and Lean Manufacturing to create The Lean Startup methodology.

MVP (Minimum Viable Product): Instead of building a perfect product in stealth, build the smallest version necessary to start learning.42

Pivot: A structured course correction to test a new fundamental hypothesis regarding the product, strategy, and engine of growth.41

Build-Measure-Learn: The feedback loop that serves as the “OODA loop” for modern founders.

This methodology reduced the capital required to launch a startup and shifted the scarcity from “money” to “validated learning.” It is now the standard operating procedure for entrepreneurs worldwide.43

6.2 Social Entrepreneurship: Mission Meets Market

Parallel to the tech boom, a movement emerged to apply entrepreneurial principles to social ills. Coined by Bill Drayton of Ashoka in the 1980s, Social Entrepreneurship seeks to solve systemic problems (poverty, sanitation, education) using market mechanisms rather than charity.44

Intrapreneurship also gained traction as large corporations, terrified of being “Schumpetered” by startups, sought to foster internal innovation. Coined by Gifford Pinchot, intrapreneurship involves giving employees the autonomy and resources to act like entrepreneurs within the safety of the firm.46

6.3 The Gig Economy: The Algorithm as Manager

The most recent evolution is the Gig Economy, or the “Platform Economy.” Facilitated by ubiquitous smartphones and platforms like Uber, Upwork, and Fiverr, this model fractures the traditional job into discrete “gigs” or tasks.47

While often framed as “new,” the Gig Economy is structurally a return to the pre-industrial “putting-out” system or piecework. The difference is the intermediary: instead of a merchant, it is an algorithm.

Scale: By 2023, independent workers contributed $1.27 trillion to the US economy.49

The Paradox: It offers the autonomy of the entrepreneur (flexible hours, no boss) but transfers the risk of the entrepreneur (fluctuating income, no benefits) to the worker, often without the potential for the upside (equity/profit) that defines true entrepreneurship.50

This represents a democratization of Knightian uncertainty. Millions of individuals now manage the volatility of their own income streams, effectively becoming micro-entrepreneurs of their own labor, navigating a market cleared not by human negotiation but by dynamic pricing algorithms.

Conclusion

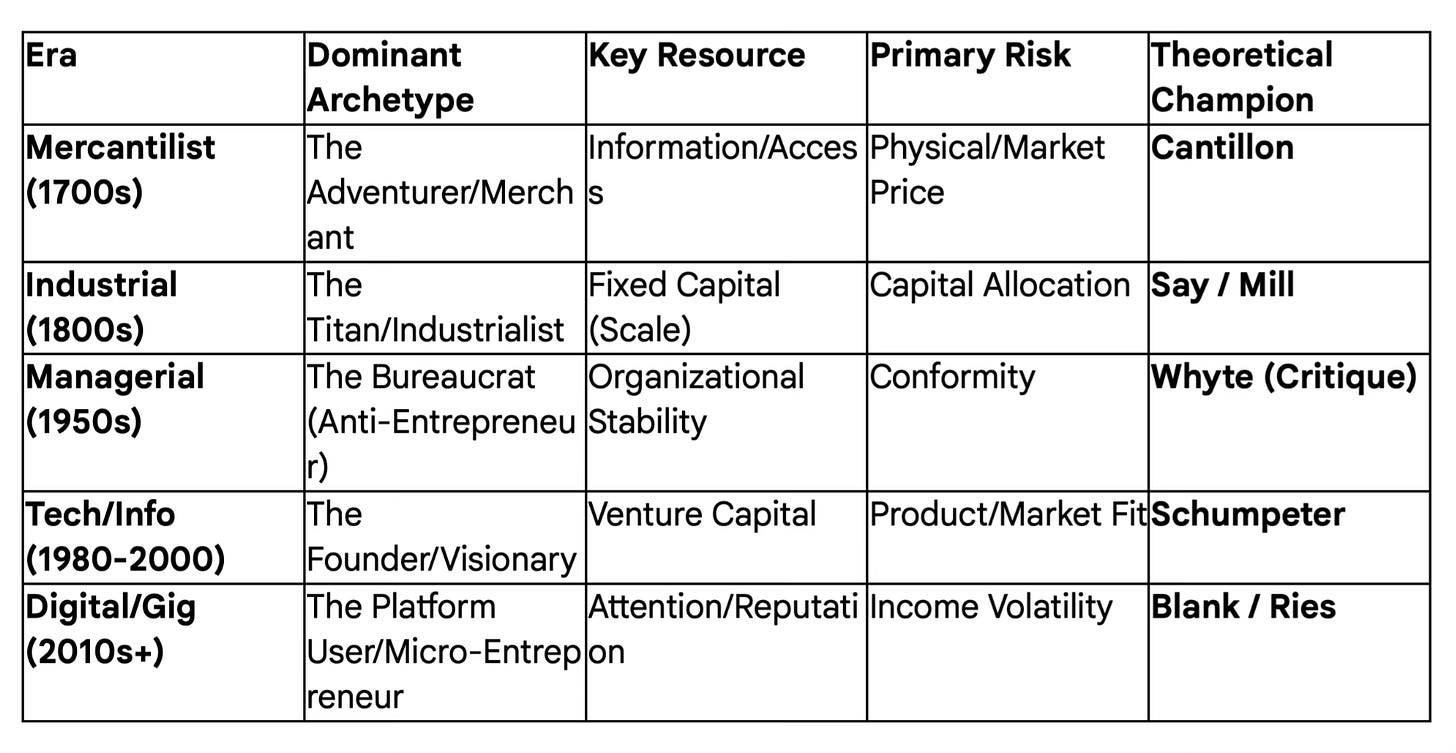

The history of entrepreneurship is a history of human agency grappling with the unknown. From the 18th-century French farmer betting on a harvest to the 21st-century software founder betting on a user base, the core thread is uncertainty.

Theory: We have evolved from Cantillon’s “Risk Bearer” to Say’s “Manager,” to Schumpeter’s “Disruptor,” and finally to the modern “Hypothesis Tester” of the Lean Startup.

Practice: We have moved from the “Great Man” theories of the Robber Barons to the systemic, venture-backed ecosystems of Silicon Valley, and now to the decentralized, algorithmic coordination of the Gig Economy.

What remains constant is the function. The entrepreneur is the society’s buffer against the future. They are the agents who volunteer to step out of the “circular flow” of the status quo, bearing the weight of the unknown in exchange for the chance to shape what comes next.

As technology accelerates the pace of change (Schumpeter’s gale blowing ever harder), the role of the entrepreneur, the alert, adaptive, risk-bearing agent, becomes not just an economic niche, but a survival skill for the modern era.

Table 3: The Evolutionary Matrix of Entrepreneurship

References:

7. Theories of Entrepreneurship, accessed on November 28, 2025, https://ebooks.inflibnet.ac.in/mgmtp09/chapter/theories-of-entrepreneurship/

R. CANTILLON’S CONCEPT OF THE ENTREPRENEUR - International Days of Statistics and Economics, accessed on November 28, 2025, https://msed.vse.cz/msed_2024/article/msed-2024-763-paper.pdf

To be or not to be: The entrepreneur in neo-Schumpeterian growth theory - EconStor, accessed on November 28, 2025, https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/269194/1/1819517756.pdf

(PDF) Creative Destruction - ResearchGate, accessed on November 28, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/319587682_Creative_Destruction

Robber baron (industrialist) - Wikipedia, accessed on November 28, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robber_baron_(industrialist)

Organization Man: William Whyte’s Classic, Read in Multiple Parts | PDF - Scribd, accessed on November 28, 2025, https://www.scribd.com/document/47352560/http-www-ribbonfarm

VC History - Venture Forward, accessed on November 28, 2025, https://ventureforward.org/resources-for-emerging-vc/vc-history/

Risk, Uncertainty, and Nonprofit Entrepreneurship, accessed on November 28, 2025, https://nonprofitquarterly.org/risk-uncertainty-nonprofit-entrepreneurship/

Entrepreneurial Theory Based on Schumpeter and Knight - OpenSIUC, accessed on November 28, 2025, https://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1002&context=esh_2021

accessed on November 28, 2025, https://www.econlib.org/library/Enc/Entrepreneurship.html#:~:text=The%20word%20%E2%80%9Centrepreneur%E2%80%9D%20originates%20from,who%20undertakes%20a%20business%20venture.

Origin Story: When Was The Term Entrepreneurship Coined? - Ludus Mastery, accessed on November 28, 2025, https://ludusmastery.com/en/origin-story-when-was-the-term-entrepreneurship-coined/

Theories of Entrepreneurship History | PDF - Scribd, accessed on November 28, 2025, https://www.scribd.com/document/57132326/enterpreneur2

Who Coined ‘Entrepreneur’? Discover the Origin and Impact - Investopedia, accessed on November 28, 2025, https://www.investopedia.com/ask/answers/08/origin-of-entrepreneur.asp

Entrepreneurship - Wikipedia, accessed on November 28, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Entrepreneurship

Teaching Entrepreneurship and Micro-Entrepreneurship: An International Perspective - ERIC, accessed on November 28, 2025, https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1070793.pdf

Entrepreneurship - Econlib, accessed on November 28, 2025, https://www.econlib.org/library/Enc/Entrepreneurship.html

From Invention to Industrial Growth | United States History II - Lumen Learning, accessed on November 28, 2025, https://courses.lumenlearning.com/suny-jcc-ushistory2os/chapter/from-invention-to-industrial-growth/

Industrial Entrepreneurs or Robber Barons? - EconEdLink, accessed on November 28, 2025, https://econedlink.org/resources/industrial-entrepreneurs-or-robber-barons/

The Rise of American Industrial and Financial Corporations - The Cupola: Scholarship at Gettysburg College, accessed on November 28, 2025, https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1039&context=ger

From Black Swan to Black Dragon: A New CEO Playbook for Global Disruption, accessed on November 28, 2025, https://ceoworld.biz/2025/11/24/from-black-swan-to-black-dragon-a-new-ceo-playbook-for-global-disruption/

Israel Kirzner - Econlib, accessed on November 28, 2025, https://www.econlib.org/library/Enc/bios/Kirzner.html

Entrepreneurial Alertness and Discovery - George Mason University, accessed on November 28, 2025, https://departments.gmu.edu/rae/archives/VOL14_1_2001/3_yu.pdf

Schumpeter vs. Kirzner on Entrepreneurs - Mises Institute, accessed on November 28, 2025, https://mises.org/mises-wire/schumpeter-vs-kirzner-entrepreneurs

Driving the Market Process: “Alertness” Versus Innovation and “Creative Destruction”, accessed on November 28, 2025, https://mises.org/quarterly-journal-austrian-economics/driving-market-process-alertness-versus-innovation-and-creative-destruction

The Achieving Society by David C. McClelland - Institute of Developing Economies, accessed on November 28, 2025, https://www.ide.go.jp/library/English/Publish/Periodicals/De/pdf/65_02_08.pdf

Achieving Society - David Clarence McClelland - Google Books, accessed on November 28, 2025, https://books.google.com/books/about/Achieving_Society.html?id=Rl2wZw9AFE4C

David Mcclelland: Achievement Motivation – BusinessBalls.com, accessed on November 28, 2025, https://www.businessballs.com/improving-workplace-performance/david-mcclelland-achievement-motivation/

[PDF] The Achieving Society by Prof. David C. McClelland | 9781787202917 - Perlego, accessed on November 28, 2025, https://www.perlego.com/book/3019424/the-achieving-society-pdf

Max Webber - 1006 Words | Bartleby, accessed on November 28, 2025, https://www.bartleby.com/essay/Max-Webber-PK9YCMFCJMHS

Organization Man | Encyclopedia.com, accessed on November 28, 2025, https://www.encyclopedia.com/social-sciences-and-law/sociology-and-social-reform/sociology-general-terms-and-concepts/organization-man

The Organization Man 9780812209266 - DOKUMEN.PUB, accessed on November 28, 2025, https://dokumen.pub/the-organization-man-9780812209266.html

The Next New Thing: Venture Capital Stories - Computer History Museum, accessed on November 28, 2025, https://computerhistory.org/stories/the-next-new-thing/

History of private equity and venture capital - Wikipedia, accessed on November 28, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_private_equity_and_venture_capital

Impact-of-the-Bayh-Dole-Act-and-Academic-Technology-Transfer.pdf, accessed on November 28, 2025, https://bayhdolecoalition.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/Impact-of-the-Bayh-Dole-Act-and-Academic-Technology-Transfer.pdf

Preserve the Bayh-Dole Act and University Technology Transfer, accessed on November 28, 2025, https://www.aau.edu/key-issues/preserve-bayh-dole-act-and-university-technology-transfer

The Bayh-Dole Act’s Role in Stimulating University-Led Regional Economic Growth | ITIF, accessed on November 28, 2025, https://itif.org/publications/2025/06/16/bayh-dole-acts-role-in-stimulating-university-led-regional-economic-growth/

Understanding the Dotcom Bubble: Causes, Impact, and Lessons - Investopedia, accessed on November 28, 2025, https://www.investopedia.com/terms/d/dotcom-bubble.asp

Dot-com bubble - Wikipedia, accessed on November 28, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dot-com_bubble

Dot-com bubble | American Business History Class Notes - Fiveable, accessed on November 28, 2025, https://fiveable.me/american-business-history/unit-11/dot-com-bubble/study-guide/piqV37x0r5cfCmb0

Understanding the Lean Startup Methodology - Helio, accessed on November 28, 2025, https://helio.app/product-discovery/product-management-techniques/lean-startup-methodology/

It only took 20 years, but the Strategic Management Society now Believes the Lean Startup is a Strategy - Steve Blank, accessed on November 28, 2025, https://steveblank.com/2025/10/30/it-only-took-20-years-but-the-strategic-management-society-now-believes-the-lean-startup-is-a-strategy-i-got-an-award-for-it/

Lean startup - Wikipedia, accessed on November 28, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lean_startup

What is the Lean Startup Methodology? - HYPE Boards, accessed on November 28, 2025, https://www.viima.com/blog/lean-startup

Social Entrepreneurship - The Philea Virtual Library, accessed on November 28, 2025, https://philea.issuelab.org/resources/15869/15869.pdf

11 Inspiring Examples of Social Entrepreneurship - Career Addict, accessed on November 28, 2025, https://www.careeraddict.com/social-entrepreneurship-examples

Contemplating the Gap-Filling Role of Social Intrapreneurship, accessed on November 28, 2025, https://scholarsbank.uoregon.edu/bitstreams/449d3074-c5e5-439e-9f41-9771b251d6fc/download

The Emergence of the Gig Economy - Ai Group, accessed on November 28, 2025, https://cdn.aigroup.com.au/Reports/2016/Gig_Economy_August_2016.pdf

Gig economy - Wikipedia, accessed on November 28, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gig_economy

Understanding the Gig Economy: Flexible Jobs Explained - Investopedia, accessed on November 28, 2025, https://www.investopedia.com/terms/g/gig-economy.asp

Gig Economy: How It Came to Be and Where It Is Going - EasyStaff, accessed on November 28, 2025, https://easystaff.io/gig-economy-how-it-came-to-be-and-where-it-is-going

(PDF) EXPLORING THE GROWTH OF FREELANCE AND GIG WORKFORCES: IMPACTS ON EMPLOYMENT MODELS AND BUSINESS RISKS - ResearchGate, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/385074343_EXPLORING_THE_GROWTH_OF_FREELANCE_AND_GIG_WORKFORCES_IMPACTS_ON_EMPLOYMENT_MODELS_AND_BUSINESS_RISKS